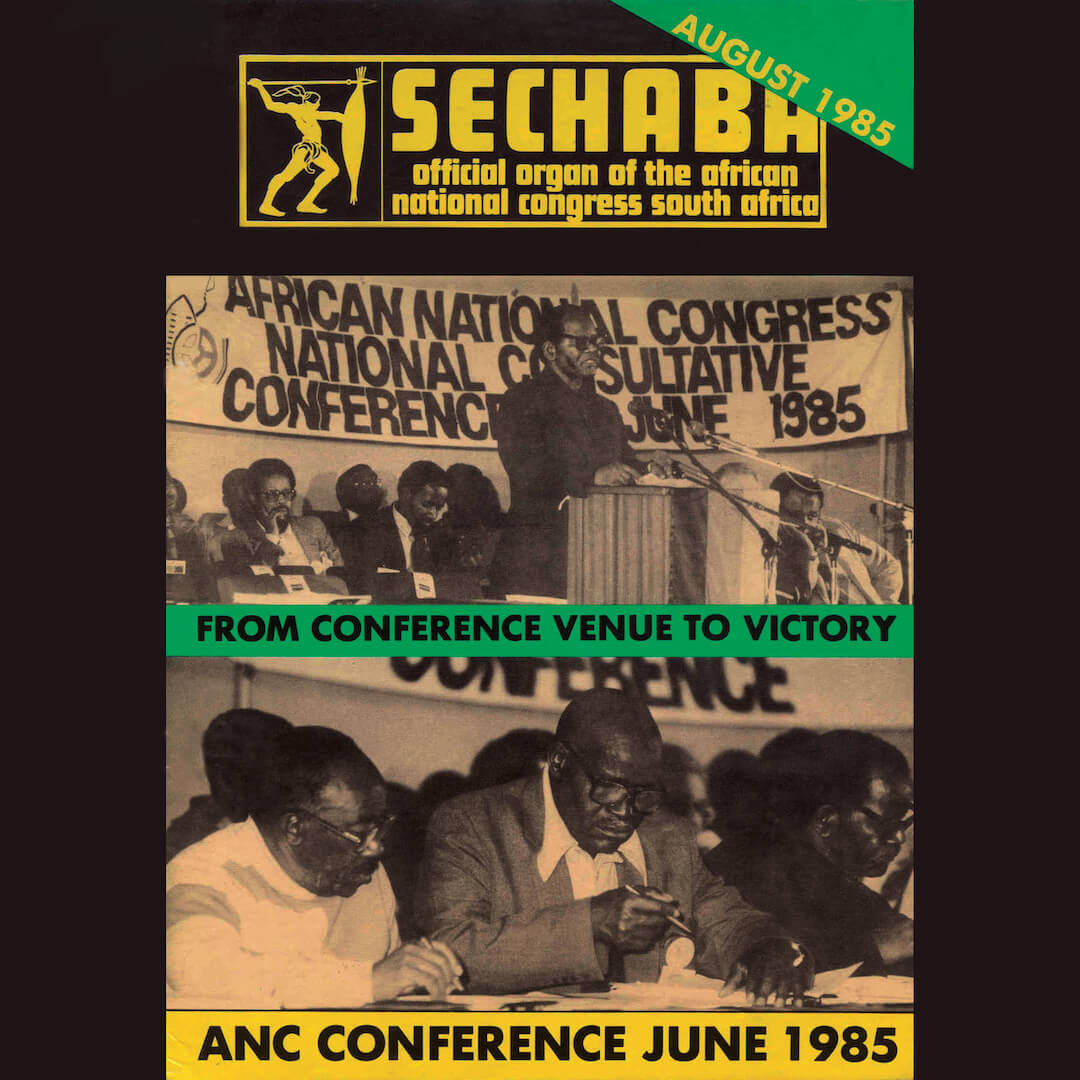

In the mid-1980s, the state of unrest and political violence in South Africa was reaching new heights. International pressure against the government was also growing. At the ANC’s National Consultative Conference in the town of Kabwe, Zambia in June 1985, Acting President, Oliver Tambo, made two appeals. The first was to make South Africa ungovernable, intensify popular mobilisation and the armed struggle, and strengthen international sanctions. The second was to ensure that the ANC was prepared with a clear constitutional vision of a new South Africa if conditions for negotiations were created. Tambo received a mandate to pursue both strategies. Umsebenzi , the mouthpiece of the South African Communist Party (SACP), spoke of the spirit of unity and sense of forward momentum that the

conference created.

In late 1984, Nelson Mandela, who had been a prisoner for over two decades, began to request a meeting with President PW Botha. Mandela was clear that he was not requesting this meeting with ‘ Die Groot Krokodil’ (The Big Crocodile) on behalf of the ANC. Instead, he wanted to open a channel and lay the groundwork for formal negotiations between the ANC and the government. Botha did not accede to a meeting, but, in 1985, he offered to release Mandela if the prisoner unconditionally rejected the armed struggle. This was the second such offer. Mandela again refused, declaring in a statement read by his daughter Zindzi: “I cannot sell my birthright, nor am I prepared to sell the birthright of the people to be free … Only free men can negotiate.” The first meeting between Mandela and Botha eventually took place in 1989.

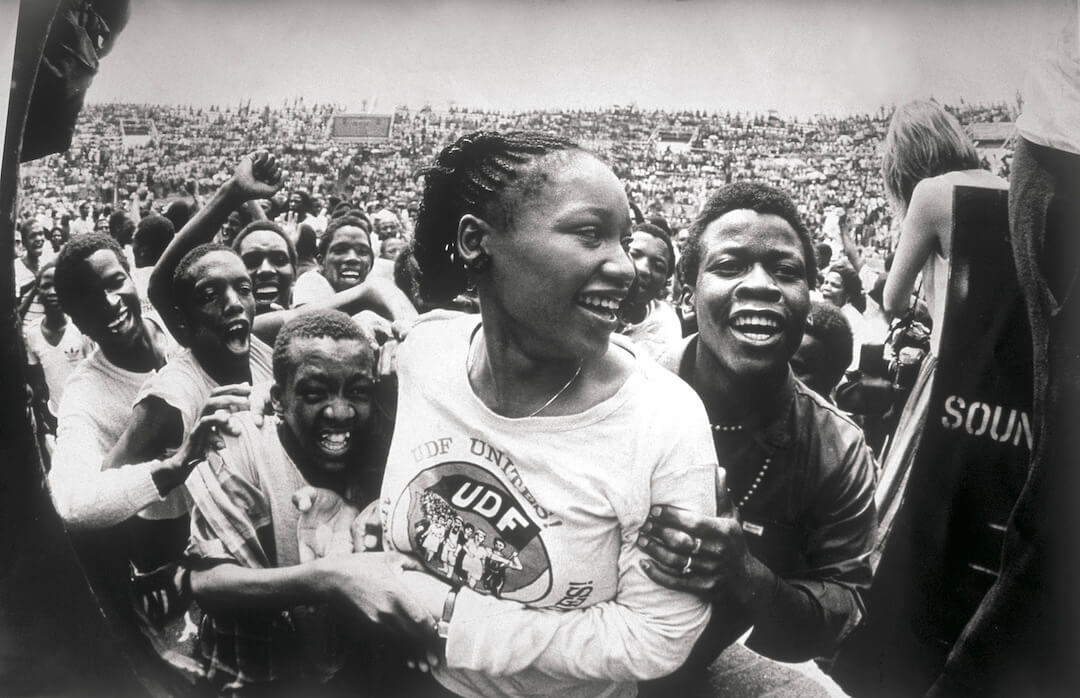

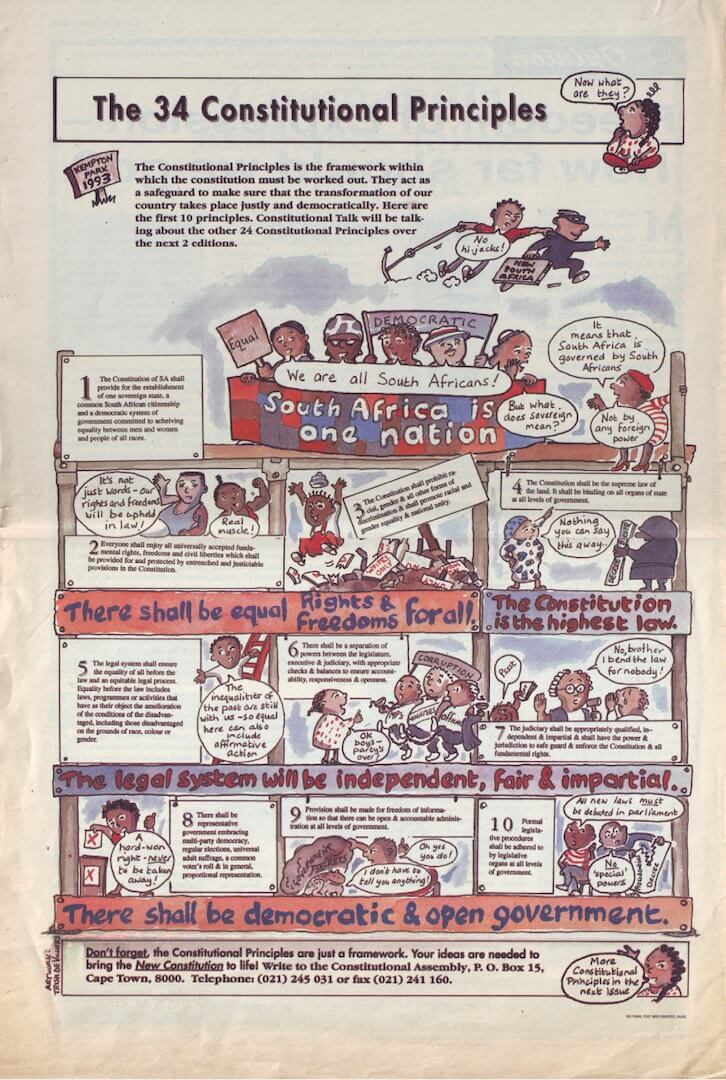

This was the first printed copy of the Constitutional Guidelines for the ANC’s in-house seminar from 4 to 8 March 1988. It was to be handed out to the over

70 delegates who were set to attend the ANC four-day seminar in the Large Seminar Room at the University of Lusaka to discuss this important document. Until then, the ANC had been responding, or refusing to respond, to all the ‘Mickey Mouse’ proposals being made from all over the world, of how to reconcile the minority rights of white people with majority rights of black people. The Guidelines put the whole debate into a completely different format, and dealt with the need for reconstruction and transformation of South African society. At the same time, they guaranteed fundamental rights, and provided a sense of democracy,

openness and fairness.

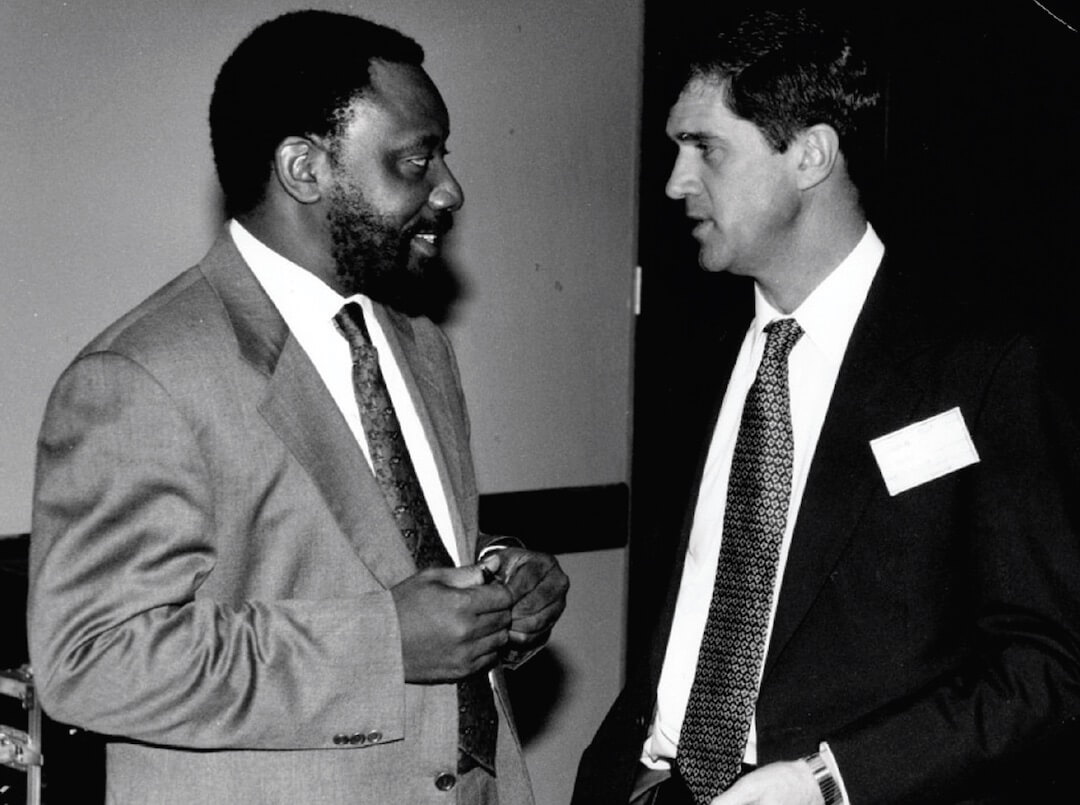

While state functionaries from the apartheid intelligence services held top-secret meetings with Mandela in prison, the ANC-in-exile embarked on a process of engagement with progressive-minded Afrikaner intellectuals, prominent businessmen as well as representatives of anti-apartheid organisations so that all concerned could ‘start listening to the other side’. In this photo taken in Dakar, Senegal in July 1987, Thabo Mbeki, the supreme diplomat entrusted by Oliver Tambo to undertake sensitive missions on behalf of the ANC, meets with Frederik van Zyl Slabbert who had recently withdrawn from Parliament as the leader of the main opposition declaring that he could no longer work in the apartheid government structures. The Dakar meeting was one of an estimated 154 secret ‘safaris’ that took place between 1985 and 1989 between white South African organisations and the ANC-in-exile.

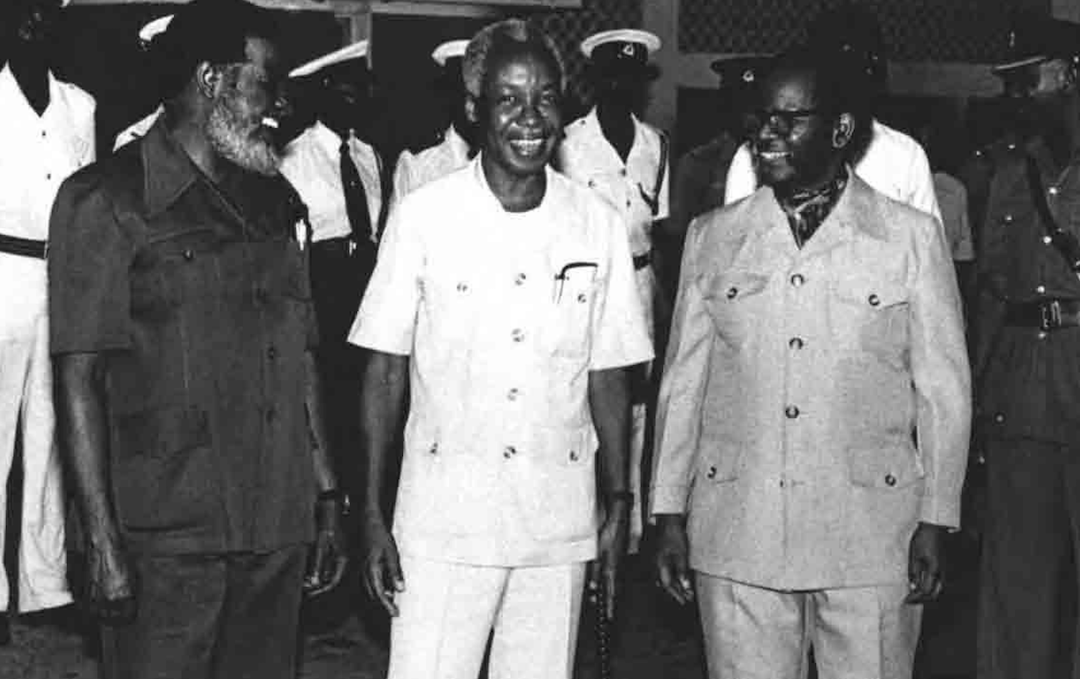

In the late 1980s, South Africa had re-imposed a State of Emergency in several parts of the country in an attempt to crush ever-increasing resistance. Oliver Tambo, the President of the ANC-in-exile, seen here with President Julius Nyerere of Tanzania (centre) and South West Africa People’s Organisation (SWAPO) President Sam Nujoma (left), crisscrossed Africa in a small aeroplane to garner support for negotiations to end apartheid. The signing of the Harare Declaration in October 1989 was a breakthrough moment. The Declaration’s five demands outlined the pre-conditions for negotiations to happen on home soil and became the bedrock for the monumental changes that were to come. One of the greatest effects of the document was the global consensus it garnered around the ANC’s own notions of democracy and equality – that is, the principle of unitary South African state with no special minority rights.

The jubilation of these marchers holding up the newspaper announcing the unbanning of the ANC and Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) captures something of the breath-taking spirit that enveloped the country after De Klerk’s speech at the opening of Parliament on 2 February 1990. The President unexpectedly announced the dismantling of the apartheid system, the unbanning of all political parties, and the imminent release of Nelson Mandela, thereby meeting many of the conditions that had been stipulated by the ANC in the Harare Declaration. The world was stunned. South Africa was set on a path of unimaginable change.

President De Klerk had unbanned political parties, freed Nelson Mandela, and was promising to negotiate a political settlement. The ANC leaders in exile, together with the internal leadership, were readying themselves to enter into talks-about-talks with the government. But why now? Several factors were at play. South Africa was in a severe economic crisis, made worse by international sanctions. The ruling NP could no longer make piecemeal reforms. The ANC acknowledged that a successful insurrection would take a long time and involve huge casualties on all sides. This delicately poised situation gave rise to a period of initial talks between the government and the ANC which later broadened to include other political groupings. Sworn enemies and competing rivals would meet to establish the process for negotiations. Central to their task was determining the constitutional vision for South Africa.

When You Come Back

President De Klerk had unbanned political parties and released Nelson Mandela. The ANC leaders in exile, together with the internal leadership, were readying themselves to enter into talks-about-talks with the government. This delicately poised situation gave rise to a period of initial dialogue between the two parties, which later broadened to include other political groupings. Sworn enemies and competing rivals would meet to establish the procedure for negotiations. Violence threatened the process from the start.

The world had been predicting a racial bloodbath in South Africa. In this extraordinary photograph, previously sworn enemies from the government and the ANC are seen standing next to each other after their first face-to-face meeting at Groote Schuur in Cape Town. Joe Slovo, the communist leader who had been the commander of an elite Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK) unit, is standing next to Dawie de Villiers, leader of the National Party (NP) in the Cape. Cheryl Carolus, prominent anti-apartheid activist who had been in and out of detention through the 1980s, and now a member of the ANC’s negotiating team, is standing behind Adriaan Vlok, Minister of Law and Order, in charge of the detentions of political activists. This moment was a concrete step towards fulfilling the mandate set out in

the Harare Declaration.

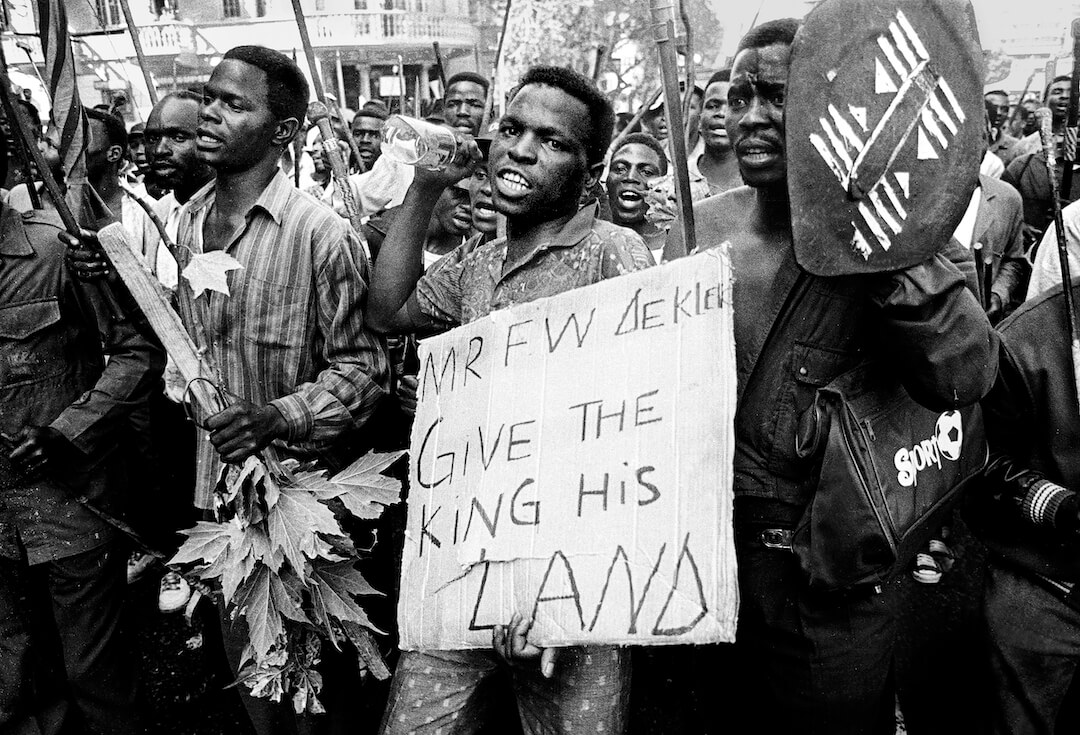

This photo captures one of the many mass marches that took place in the early 1990s to call for the unconditional release of political prisoners who were still being held in jails across South Africa. Disagreement over the definition of a political prisoner had hampered progress on the issue for many months. The ANC argued for the broadest possible definition of political prisoners. The government demanded that those prisoners convicted of killing civilians and policemen should be considered ordinary criminals . With this classification of ‘political offences’ as ‘criminal offences’, only a small percentage of political prisoners would actually be eligible for release. In addition, many exiles returned to the country unsure as to whether they would be faced with arrest and prosecution. Frustration grew within the ranks of the ANC and its allies around the issue and delayed progress in the negotiations.

By the end of 1990, the two major parties had agreed on who should be sitting at the negotiating table – all political parties; governments of the homelands and so-called independent states; the South African government as well as the National Party (NP). But there was still a dispute over what they would be negotiating. The ANC and NP held dramatically different positions on three major issues: the nature of the transition; who should draft a new constitution; and the vision for a new country. Mandela broke the deadlock in January 1991 when he called for ‘an all-party congress’ to negotiate the way forward. This offered the basis of compromise although the differences between the two parties’ constitutional proposals persisted and ultimately caused a breakdown in negotiations.

One of the greatest obstacles to negotiations remained the wave upon wave of violence that engulfed the country. A low-grade civil war between the IFP and the ANC had begun in the mid to late 1980s in Natal, but the scale and consequences of the violence increased dramatically after 1990. The war spread to the then Transvaal, and bloody battles ensued daily in the townships, especially on the East Rand between Umkhonto weSizwe (the armed wing of the ANC), the young comrades, the police, IFP supporters living in the migrant worker hostels, and armed units of AZAPO. In the course of two years, over 6 000 people lost their lives in gruesome township wars. Township residents and the ANC accused the apartheid government through the police and security forces of aiding and abetting the violence.

King Goodwill Zwelithini and Chief Buthelezi, leader of the IFP, are pictured here with supporters of the IFP in traditional Zulu dress. In May 1991, the ANC sent an open letter to De Klerk threatening to suspend negotiations unless the government met its demands for ending the violence. These included firing the ministers of security, punishing members of the security forces implicated in violence, outlawing the public carrying of traditional weapons, and releasing remaining political prisoners. A month later, concrete evidence emerged that the government had been clandestinely funding the IFP and was using the war between the IFP and ANC in Natal to pressure the ANC to make negotiating concessions. This revelation was known as Inkathagate. The ANC announced the suspension of talks with the government.

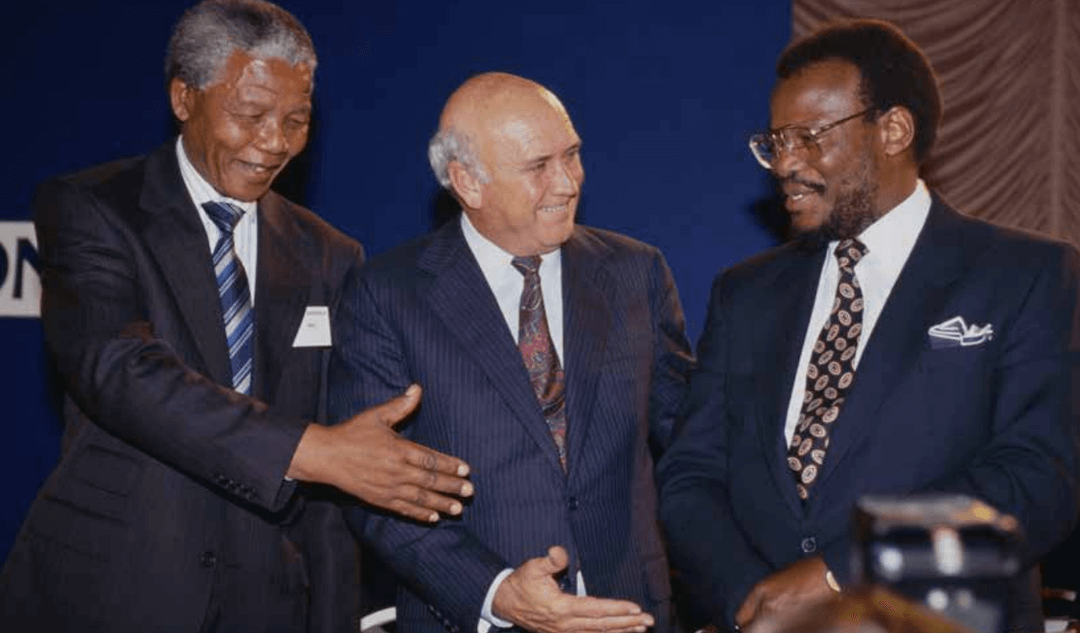

In the context of the widespread violence, political leaders across the spectrum acknowledged the need to combat the devastation. After rounds of intensive negotiations over a couple of months, 24 political groups came together to sign a National Peace Accord. This image shows the leaders of the so- called ‘big three’ political parties – the ANC, the NP, and the IFP – shaking hands at the signing on 14 September 1991, a moment considered a major break-through in negotiations. Each of the 11 designated regions in the country set up as many peace structures as deemed necessary with multiple parties sitting around the table to hammer out solutions to violence in a particular community. Peace Committees became ‘the cells of negotiations’ on the ground – ‘mini-CODESAs’. There were 263 local peace committees by 1994

Brenda Fassie and Tsepo Tshola

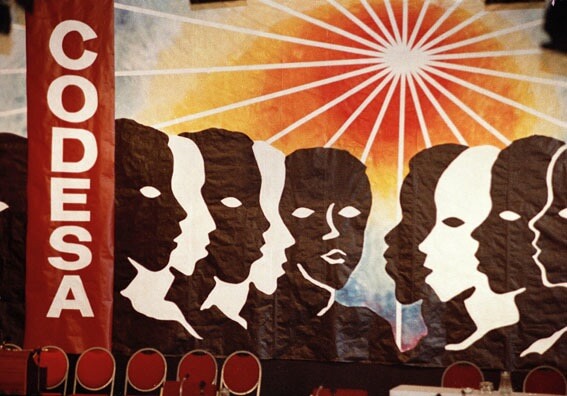

In late November 1991, after nearly two years of talks about talks, an All-Party Preparatory Meeting agreed on a permanent negotiating forum to be named the Convention for a Democratic South Africa (CODESA). The CODESA talks that began in December 1991 were a significant milestone. They were, however, beset by multiple breakdowns and deadlocks caused by the violence that engulfed the country, as well as clashes around the nature and outcomes of the constitution-making process. After the Bisho massacre, the talks collapsed.

On Friday, 20 December 1991, the drab and unimaginative World Trade Centre in Kempton Park was transformed into the first unofficial space for democratic discussion in South African history. Here, the transition from apartheid to democracy would begin. The air was electric and 19 parties and organisations – 228 delegates in

all – arrived brimming with excitement and some nervousness. Millions of ordinary South Africans watched and listened to these historic proceedings live

on television.

In the first months of 1992, political violence was worse than ever. Accusation followed counter-accusation about the causes of the rising death toll. Negotiations had also stalled over a constitutional vision for the country. The National Party clung to notions of the protection of minorities and said that an elected majority would ‘swamp the constitution-making process’. At this point, the ANC-SACP-COSATU alliance agreed on a policy of ‘rolling mass action’ – including strikes, demonstrations and boycotts – to demonstrate the extent of their mass-based support. Symbolically, the first boycott took place on 16 June 1992, the day students in Soweto had risen up in the schools 16 years previously. The government believed that this climate of ‘militant thinking’, undermined the ‘attempts of many ANC realists to negotiate in good faith’.

Ultimately, it was not the mass action campaign that shifted the situation at CODESA, but the tragedy that struck in Boipatong, a township on the East Rand. On the night of 17 June 1992, mainly IFP supporters from the KwaMadala hostel took to the streets and attacked

ANC-supporting residents in their homes and shacks in and around the Slovo Park squatter camp. Forty-nine

people – mostly women and children – were killed. Survivors of the massacre spoke about having seen members of the security forces aiding the hostel dwellers. More than 25 000 people, including local and international dignitaries, attended the mass funeral for the victims. Angry crowds lined the streets, many wearing T-shirts with the slogan ‘Boipatong Calls Us To Action’, as a line of hearses crawled from the Boipatong soccer stadium to the Sharpeville cemetery.

Cyril Ramaphosa of the ANC is seen here in deep conversation with Roelf Meyer of the NP. Meyer (who had just taken over from Gerrit Viljoen as the NP’s chief negotiator), reached out to Ramaphosa with a request for a meeting against the backdrop of the violence and the halting of negotiations. Meyer told Ramaphosa that he wanted to properly understand the ANC’s point of view, and formulate acceptable responses to ANC demands. Mandela agreed to Ramaphosa establishing a channel for maintaining quiet dialogue with a view to exploring possible solutions to the impasse. All realised that without a bilateral understanding between the ANC and the NP, there was no hope for a negotiated settlement or of overcoming the acrimony left by the disintegration of CODESA. Thus ‘the channel bilateral’ was created by these two negotiators.

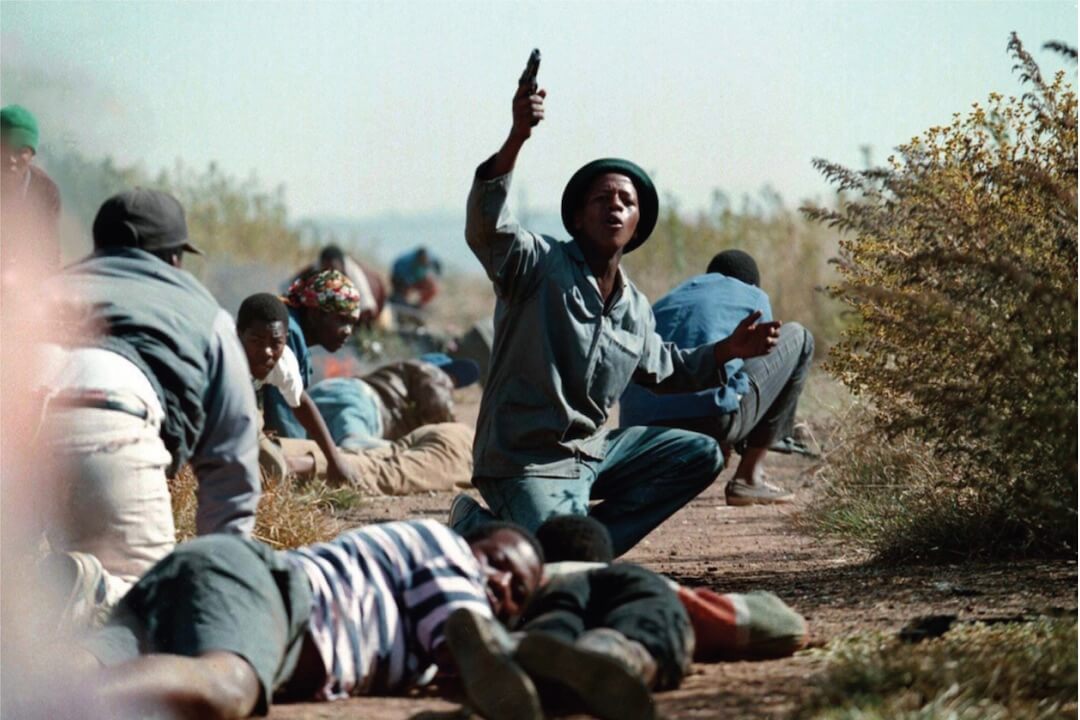

This image of protestors fleeing took place during the massacre at Bisho on 7 September 1992. On that day, the ANC had arranged a march on Bisho, the capital of the ‘independent’ Ciskei homeland as part of its continued rolling mass action campaign. Eighty thousand people participated in a protest to oust the Ciskei’s unpopular military leader, Brigadier Oupa Gqozo, hated by many as a despot. As marchers approached the Bisho stadium, Ciskeian soldiers opened fire and 29 protestors died and over 200 were injured. The media accused ANC leaders of having been ‘reckless’ in leading the march while also recognising that it was the government’s ‘surrogates’ who were responsible for the deaths of so many people.

Hover over the yellow speech bubbles on the photographs to hear from the people involved.

After the collapse of CODESA II, behind the scenes talks between the ANC and NP became the main channel to break the deadlock between the two principal parties. Eventually, on 1 April 1993, 26 political groupings, as well as the homeland governments, gathered in a new negotiating structure known as the Multi-Party Negotiating Process (MPNP). On 10 April, Chris Hani, leader of the South African Communist Party, was murdered and the country teetered on the brink of war. Miraculously the difficult negotiations continued. After seven and a half months an Interim Constitution was adopted – the country’s very first democratic constitution.

The Record of Understanding was hailed as a victory that allowed negotiations to resume. Two of the biggest problems had been resolved. Firstly, there was now acceptance of a vision of a united, non-racial society with a parliamentary democracy, coupled with a Bill of Rights rather than the National Party’s (NP’s) proposed power-sharing arrangement. Secondly, everyone agreed on a two-stage constitution-making process with an interim and then a final constitution based on agreed principles to be enforced by the Constitutional Court. It took a further six months for the parties to decide on the form of negotiations. On 1 April 1993, 26 political groupings as well as national and homeland governments gathered in a new negotiating structure known as the Multi-Party Negotiating Process (MPNP)

Only days after negotiations resumed, events outside of the World Trade Centre again threatened to derail the process. Chris Hani, the former commander of Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), general secretary of the Communist Party and charismatic leader in the ANC, was assassinated outside his home in Boksburg in broad daylight. Hani had a reputation for courage as a soldier who had been in battle. He was a thoughtful and powerful orator who regularly brought crowds to their feet. The country was plunged into a crisis after Hani’s assassination. “Nithi sixole kanjani amabhunu abulale uChris Hani? (How do you expect us to be at peace when the Boers have killed Chris Hani?) was the cry that rang out from angry young comrades who took to the streets. South Africa appeared to be out of control.

This photograph of Bophuthatswana President, Lucas Mangope, CP leader, Ferdi Hartzenberg, IFP leader, Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi, and Bophuthatswana delegate, Rowan Cronj é , was taken when the homeland governments and right-wing Afrikaner parties formed COSAG. These strange bedfellows were united in their determination to ‘draw a line against the manipulation of the talks’ by the ANC and the government. COSAG members walked out of the MPNP, demanding that their objections be dealt with before the talks could resume. They pressed for a federal constitution to preserve the rights of ethnic minorities, especially the Zulu and white communities. Talk of secession entered the political arena.

After the negotiating forum rejected the idea of an Afrikaner homeland, hundreds of Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging (AWB) supporters, clad in khaki military apparel and armed to the teeth, marched on the World Trade Centre. Pandemonium broke out when an armoured car burst through the plate-glass door of the Centre. Once inside, AWB members entered the negotiations chamber and assaulted negotiators both physically and verbally. They also destroyed property and painted slogans on the walls. Witnesses accused the police of simply standing by. Roelf Meyer and Dawie de Villiers (both ministers in the NP government), negotiated with the AWB to leave the building by promising that no arrests would be made.

Under the new fortress-like conditions at the World Trade Centre, the various parties engaged in intense negotiations. Joe Slovo, one of the founders of Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK) and former general secretary of the SACP, seen here with Ramaphosa, became known for his pragmatism in dealing with the thornier issues. The man who had argued for ‘no middle road’ in the 1960s, now set out a scenario for a negotiated settlement which contained concessions – later known as the ‘sunset clauses’ – that were arguably pivotal in paving the way for a peaceful transition. Slovo proposed that the ANC accede to De Klerk’s proposal to have a Government of National Unity (GNU) for a period of five years, with the different parties being represented in proportion to their election results. Pallo Jordan argued strongly against this proposal.

As dawn was breaking on 18 November 1993, exhausted negotiators danced in the corridors of the World Trade Centre having just finalised the Interim Constitution. Success at last! They had spent the last few days and nights hammering out final solutions and significant concessions had been made on all sides. A critical feature agreed to was the creation of a set of Constitutional Principles – the final constitution had to adhere to these principles. Four days later, the Interim Constitution was passed almost unanimously by the racially segregated Tricameral Parliament. This voluntarily and legally abolished the Parliament that had excluded the black majority, thus concluding a unique negotiated revolution to bring about a united, non-racial democracy. The 142-page document was South Africa’s first democratic constitution.

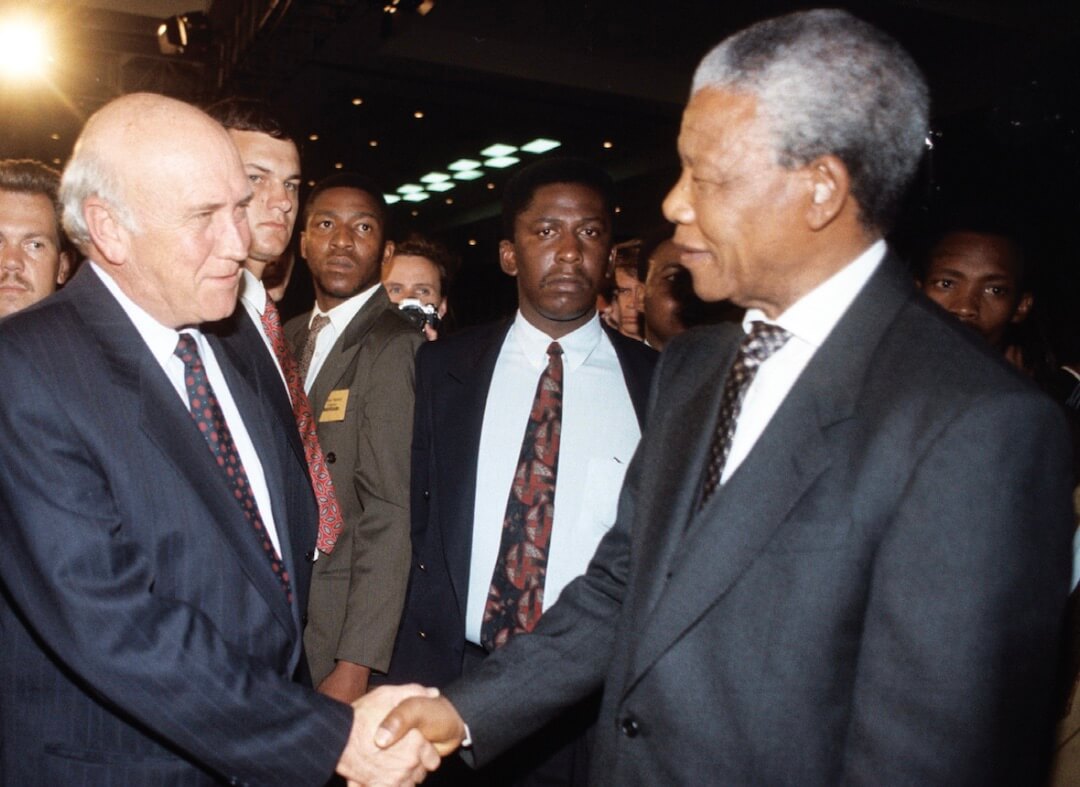

Over the years, relations between De Klerk and Mandela had not always been good. But each was aware of the need to show firm and friendly leadership. Here they are shown shaking hands at an early meeting of the TEC – which they co-chaired – towards the end of 1993. The TEC was a multi-party body set up to prepare for the transition to a democratic order in South Africa. This interim executive structure would rule until the first democratic elections. According to the ANC, South Africa was now ‘firmly and irreversibly set on course for transition to democracy’ and free political activity was now possible. The end was in sight for apartheid and

NP rule.

Freedom is coming tomorrow

By the start of 1994 the end of apartheid was in sight. The Transitional Executive Council (TEC) was a multi-party body that was set up to oversee the running of the country to ensure free political activity in the lead up to the first democratic elections. While this was an exciting, hopeful time, there were still serious obstacles to be overcome. The right-wing threatened war, the generals demanded amnesty, there was a coup in Bophuthatswana and the IFP refused to participate in the elections until the eleventh hour. Ultimately, sufficient peace prevailed for democratic elections to take place.

In May 1993, General Constand Viljoen (in the centre of this photo ) , former chief of the apartheid army, launched the Afrikaner Volksfront (AVF). This ‘People’s Front’ united several right-wing Afrikaner groupings. They demanded an independent Volkstaat or homeland for those who shared the same language and conservative values. The AVF also called fo r a ‘Third War of Independence’ to disrupt elections. Leaders urged right-wingers to stockpile arms for a siege, and made clear that a civil war would involve acts of sabotage and harassment of farmworkers and black people in general. Viljoen reportedly had around 60 000 trained paramilitary personnel at his command and the support of a high percentage of the South African Defence Force (SADF). The threat of a bloodbath was ever-present.

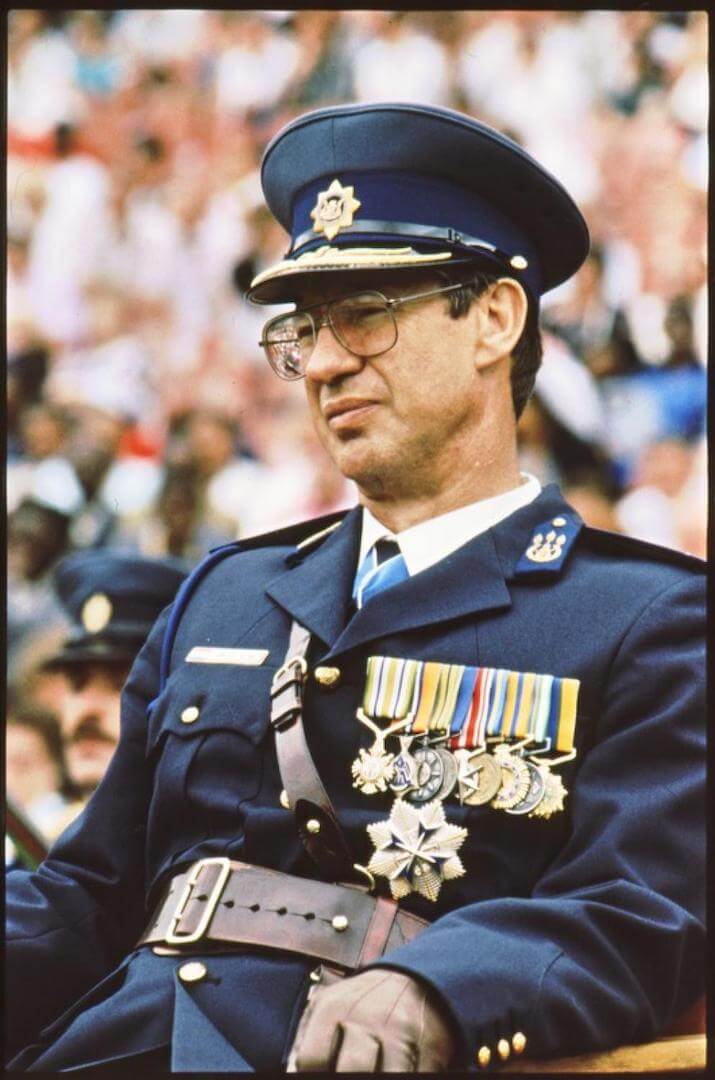

The army generals had hoped that there would be a general amnesty clause in the Interim Constitution that would protect them against prosecution for actions undertaken in the course of their duties during apartheid. But the final November text of the Interim Constitution was silent on the matter. The generals felt betrayed. They stated that they would defend the democratic elections against projected attacks, but refused to run the risk of being sent to jail in the new democracy for following the instructions of their former political leaders. They would simply resign their commissions and go abroad. An epilogue was added to the Interim Constitution on the eve of the democratic elections to avoid a further crisis.

In this cropped version of the shocking photograph of injured Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging ( AWB) members, Colonel Alwyn Wolfaardt raises his hands in surrender. Wolfaardt and his two colleagues had driven around at the back of an AWB convoy that had responded to President Lucas Mangope’s call for military assistance to crush a mutiny in the independent state of Bophuthatswana. When the AWB randomly sprayed bullets into people’s houses, members of the Bop Defence Force returned fire and shot Wolfaardt in the arm, Fourie, the driver, in the neck, and Uys in the leg. Shortly after this photograph was taken, a local police officer, Ontlametse Menyatsoe, shot dead all three at point blank range in front of television cameras. This brutal moment sent shock waves through South Africa and the world.

A month before the country’s first democratic election, 20 000 members of the IFP armed with traditional Zulu weapons took part in a march to the ANC headquarters at Shell House in Joburg’s city centre. The march marked the launch of the IFP’s anti-election campaign and was also in support of King Goodwill Zwelithini’s demands for an independent Zulu kingdom. Amidst claims that the IFP were planning to storm Shell House and attack those inside, the ANC security guards opened fire as the marchers approached the building. Minutes later, volleys of gunfire sent a huge crowd at the Library Gardens rally scattering for cover. Eight people were killed immediately and 84 were injured. A further 11 people were killed in the chaos that followed. The incident led to the IFP finally agreeing to participate in the elections at the eleventh hour.

27 April 1994: the day of South Africa’s first multiracial democratic elections. Almost 20 million South Africans queued for hours to put their ‘X’ on ballot slips to end nearly 350 years of racial polarisation, oppression and conflict. Eighteen million of those people were voting for the first time in their lives. Some disabled voters were brought to the ballot boxes in wheelbarrows, demonstrating their determination to vote. Prophets of doom expected bloodshed and civil strife. Instead, peace prevailed and the elections took place in an atmosphere of excitement. The words of an unemployed black man in the queue, “Now I am a human being,” sum up the heartfelt jubilation of the day.

On 10 May 1994, thousands of South Africans gathered on the lawns in front of the Union Buildings in Pretoria to celebrate the inauguration of South Africa’s first democratically elected President. Before addressing them, Mandela danced briefly to the music of the African Jazz Pioneers. In a carnival atmosphere, a group of youths ran across the lawn holding aloft a coffin with “hamba kahle apartheid” painted on the side. President Mandela then introduced his two Deputy Presidents, Thabo Mbeki and FW de Klerk and lifted their arms into the air in a sign of victory and unity. “Wat verby is, is verby” (What is over, is over), the newly inaugurated Mandela declared. This is one of the many iconic photos that marked the day.

ReferencesBarnard, N (2015) Secret Revolution: Memoirs of a Spy Boss, as told by Tobie Wiese

Barnes, C and De Klerk, E (2002) “South Africa’s multi-party constitutional negotiation process”, Accord: An International Review of Peace Initiatives , Issue 13

Butler, A (2008) Cyril Ramaphosa , Jacana Media, Johannesburg

Corder, H (1994) “Towards a South African Constitution” , Modern Law Review

Davenport, T (1991) South Africa: A Modern History , 4th ed, Macmillan, London

De Klerk, FW (2000) The Last Trek – A New Beginning: The Autobiography , Pan Macmillan

Ebrahim, H (1998) The Soul of a Nation , Oxford University Press, Cape Town

Eldridge, M (1996), “Now wasn’t the times: the ANC ‘s 1994 Election Campaign in South Africa’s Western Cape Province, BA Honours, Stanford University

Friedman, S (ed.) (1993) The Long Journey: South Africa’s quest for a negotiated settlement , Ravan Press, Johannesburg

Gevisser, M (2008) Thabo Mbeki: The Dream Deferred , Jonathan Ball Publishers, Johannesburg

Gevisser, M (2009) A Legacy of Liberation: Thabo Mbeki and the Future of the South African Dream

Gerhart, G and Glaser, C From Protest to Challenge –- A documentary history of African Politics in South Africa, 1882-1990 , Volumes 6: Challenge and Victory 1980-1990, Hoover Institution Press; Volumes 5-6, Indiana University Press

Ginsberg, M “South African Labor Marching Again” in Solidarity, https://solidarity-us.org/atc/63/p2359/

Hofman, J (2007) “The Constitutional Assembly Database Project – Resurrecting a Database Ten Years On,” International Journal of Legal Information : Vol. 35: Iss. 1, Article 8, p. 84. Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/ijli/vol35/iss1/8

Klug, H (2000) Negotiating New Legal Orders: Poland’s Roundtable and South Africa’s Negotiated Revolution

Lodge, T (2003), “How the South African Electoral System was Negotiated” in Journal of African Elections

Makgetla, T and Jackson, R, (1993) “Negotiating divisions in a divided land: Creating provinces for a new South Africa, 1993” in Innovations for Successful Societies

Mandela, N (1995) A Long Walk to Freedom , Abacus, London

Mawson, A (2010), Organising the first post-apartheid election: South Africa

Murray, C (2011) “A Constitutional Beginning: Making South Africa’s Final Constitution” in Law Review , 809, 23 University of Arkansas at Little Rock L. Rev, 2001. Available at: http://lawrepository.ualr.edu/lawreview/vol23/iss3/3

Nicol, M (1997) The Making of the Constitution , Churchill Murray Publications, Cape Town

Pahad, A (2014) Insurgent Diplomat: Civil Talks or Civil War, Penguin Random House

Piper, L, (2015) “The Politics of Zuluness in the Transition to a Democratic South Africa” PhD

Reader’s Digest Association (1995) Readers Digest Illustrated History of South Africa , Reader’s Digest Association, Cape Town

Sachs, A (2018) Oliver Tambo’s Dream: Four lectures by Albie Sachs

Segal, L and Cort, S (2011) One Law, One Nation: The Making of the South African Constitution , Jacana Media South Africa

Simpson, G (1994), “Proposed Legislation on Amnesty/Indemnity and the establishment of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission.”

Taylor, R (2002) Justice Denied: Political Violence in KwaZulu-Natal after 1994 in Violence and Transition Series , Vol. 6

Shaik, M (2020) The ANC Spy Bible , Tafelberg

Sisulu, E (2002) Walter & Albertina Sisulu: In Our Lifetime , David Phillip, Claremont

Slovo, J (1995) Slovo: The Unfinished Autobiography , Ravan Press, Johannesburg

Sparks, A (1995) Tomorrow is Another Country: the Inside Story of South Africa’s Road to Change , Struik

Spitz, R and Chaskalson, M (2000) The Politics of Transition: A hidden history of South Africa’s negotiated settlement , Witwatersrand University Press, Johannesburg

Waldmeir, P (1998) Anatomy of a Miracle , Penguin, London

Woolman, S and Bishop, M (2013) Constitutional Law of South Africa , South Africa, 2 nd Edition, Revision Service 5, Juta & Co, Cape Town

Filmography

Serfontein, H Breaking the Fetters, produced for Fokus Suid CC

Constitution Hill Trust (2019) Constitution Hill Trust Oral History Project

Du Preez, M Oral History Project, SABC Interviews

O’Malley, P Political Interviews

De Wet, P, transcript of interview with General Tienie Groenewald, accessed May 2020, http://kora.matrix.msu.edu/files/52/325/34-145-E-31-AL3283_A2.2.6.1.pdf

O’ Malley The Heart of Hope, https://omalley.nelsonmandela.org/omalley/

South African History Online, https://www.sahistory.org.za/

The Observation Post Modern South African Military History, https://samilhistory.com/

Online articles

APLA cadre apologises to families of East Cape victims, 1 April 1998, SAPA, accessed May, https://www.justice.gov.za/trc/media/1998/9804/s980401c.htm

Camay, P and Gordon, A.J, “The National Peace Accord and its Structures South Africa Civil Society and Governance” Case Study No. 1, accessed May 2020, https://omalley.nelsonmandela.org/omalley/index.php/site/q/03lv02424/04lv03275/05lv03294/06lv03321.htm

Du Preez, M, “Viljoen reveals just how close SA came to war”, Sunday Independent , 24 March 2001, accessed May 2020, https://www.iol.co.za/news/politics/viljoen-reveals-just-how-close-sa-came-to-war-62836

Keller, B, “South African Rightists Rally Behind Ex-Generals”, New York Times , 6 May 1993, accessed May 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/1993/05/06/world/south-african-rightists-rally-behind-ex-generals.html

Maier, K, “SA police generals supplied arms to Inkatha”, Independent UK , 19 March 1994, accessed May 2020, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/sa-police-generals-supplied-arms-to-inkatha-1430001.html

Savage, K, “Negotiating the release of political prisoners in South Africa”, Research Report written for the Northern Ireland Programme at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard, 2000”, accessed May 2020, https://www.csvr.org.za/docs/correctional/negotiatingtherelease.pdf

Taunyane, O, “Limpho Hani and the SACP are deeply disappointment at the court’s ruling to release Chris Hani’s murderer Janusz Walus on parole”, accessed May 2020, http://www.capetalk.co.za/articles/12129/it-s-a-very-sad-day-in-south-africa-says-limpho-hani-of-janusz-walus-release

Online documents